Overview

CJPME is delighted to release the results of a Canada-wide survey it has co-sponsored with the Canadian Arab Federation and the Arab Canadian Lawyers Association.

CJPME is delighted to release the results of a Canada-wide survey it has co-sponsored with the Canadian Arab Federation and the Arab Canadian Lawyers Association.

The survey report is available in .pdf format here, and is presented in its entirety below.

The survey was conducted by EKOS Research Associates between between May 26-31, 2021, with a random sample of 1,005 Canadian adults aged 18 and over. The margin of error associated with the in-scope sample is plus or minus 3.1 percentage points, 19 times out of 20. The raw data from the EKOS poll can be found via the following two links. The first file below contains the "residuals" (i.e. the results including the "no response" and "do not know" answers); the second file contains the stats with the "residuals" removed:

Note that all charts presented on this page are public domain - free of copyright restrictions.

Executive Summary

A recent survey of Canadians confirms that, like many minority groups, Arabs in Canada face systemic racism. This racism is broadly present in Canadian society, potentially affecting Arabs’ ability to immigrate to Canada, participate and thrive fully as citizens, enter into the workforce, and to live free of preconceptions about their lives and morals.

EKOS Research Associates (https://www.ekos.com/) conducted the national online survey of 1,005 Canadians, between May 26-31, 2021, on behalf of Canadians for Justice and Peace in the Middle East (http://cjpme.org), the Canadian Arab Federation (www.facebook.com/CAF50/), and the Arab Canadian Lawyers Association (http://www.canarablaw.org/). The margin of error associated with the sample is plus or minus 3.0 percentage points, 19 times out of 20.

The organizations sponsoring this survey have long observed that Arabs in Canada face systemic racism in Canada. They also had reason to suspect that this racism manifested itself in many different ways, including: 1) opposition to immigration from Arab countries, 2) racial profiling of Arabs in Canada, 3) barriers to the Canadian employment market for Arabs, and 4) negative stereotypes about Arabs and Arab culture.

Survey respondents were asked eight questions designed to elicit their perceptions – and indicators of latent prejudices – toward Arabs. To achieve this, many questions used a “split sample,” where a randomized portion of the respondents were asked a question about Arabs, and the other respondents were queried on the same point in the general case. Overall, the survey revealed a disturbing trend of racist attitudes toward Arabs, especially among specific sectors of Canadian society.

Attitudes toward Arabs and Arab immigration

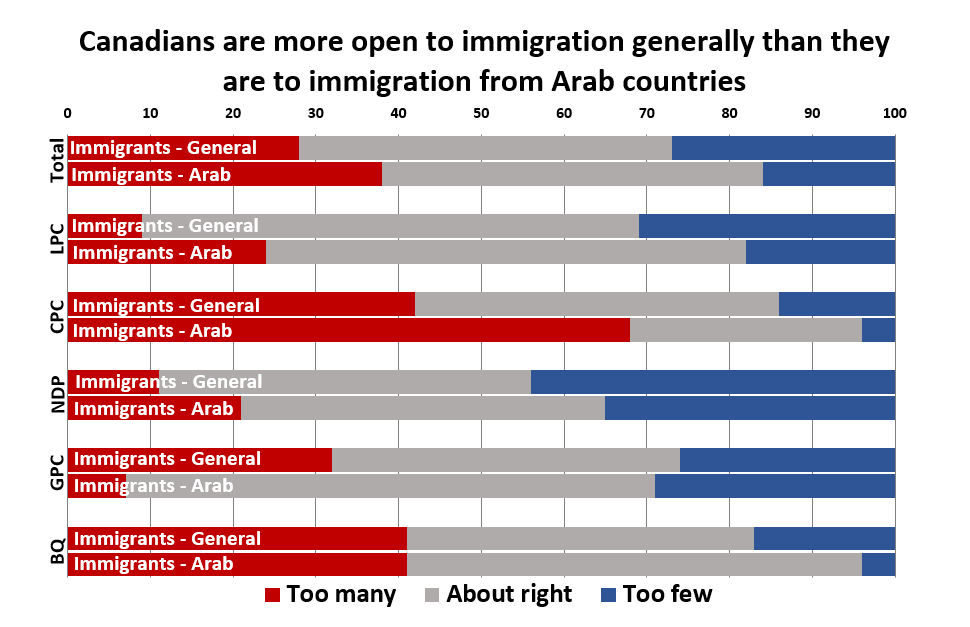

The survey results indicate that Canadians hold more negative views on immigration from Arab countries, compared to immigration in general. Canadians were 10% more likely to say there are too many Arab immigrants, as compared to their view on immigrants generally. This position is extremely polarized by respondents’ political party support. Overall, 38% of Canadians feel there are too many Arab immigrants, as compared to 68% of Conservative supporters, 24% of Liberal supporters, and 21% of NDP supporters.

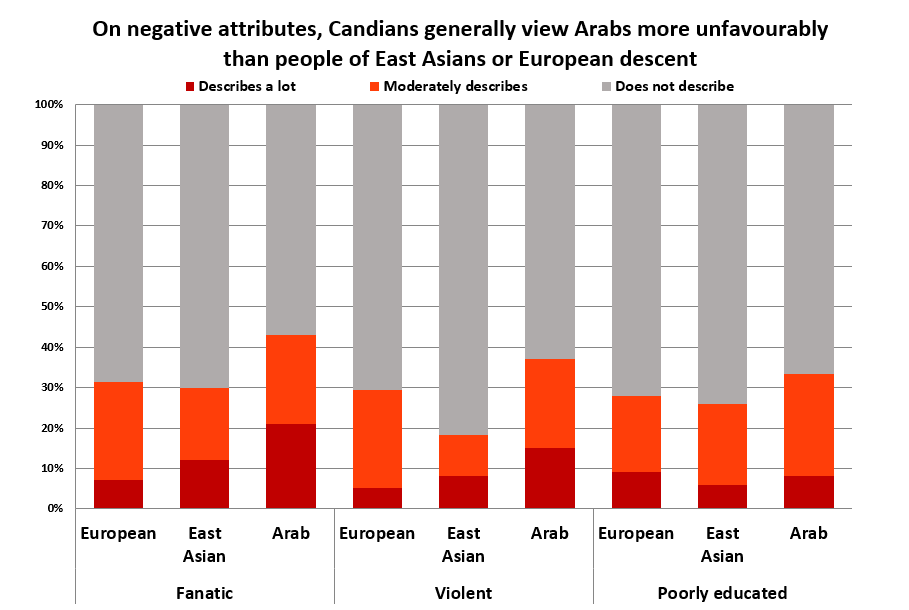

The survey also reveals that Canadians tend to view Arabs much more negatively than people of other backgrounds, with Arabs consistently rated lower on positive stereotypes, and higher on negative stereotypes. Compared to East Asians and Europeans, Arabs were much less likely to be perceived as tolerant, adaptable, open-minded, or as contributing to the community. Similarly, Arabs were twice as likely to be seen as violent (15%), fanatic (21%), and oppressive towards women (48%) than East Asians or people of European descent. Conservative and Bloc Québécois (BQ) supporters hold the least positive impression of Arabs, while NDP supporters see Arabs most positively.

Perceptions of discrimination against Arabs

A striking 79% of Canadians acknowledge that prejudice against Arabs to be somewhat of a problem or a serious problem. This number is slightly less than the number of Canadians (83%) who consider prejudice overall against racialized people to be a problem. While it is encouraging that so many Canadians acknowledge the problem of anti-Arab racism, it is also likely suggestive of the severity of the problem.

Fortunately, the survey revealed that Canadians are generally uncomfortable with racial profiling when it comes to increased public security measures. Canadians are less likely to support increased measures (visa applications, airport security, allowing police to stop and question in the street, etc.) when those measures are targeted specifically at racialized groups, compared to when the policies are applied to the general population. For example, whereas 54% of Canadians support greater airport security, less than half that number would support greater airport security that targeted racialized groups (25% for Arabs, 26% for East Asians).

Nevertheless, Conservative and BQ supporters were much more likely to support racial profiling. For example, Conservative voters support targeting Arabs with greater scrutiny when it comes to visa applications (71%), the finances of civic organizations (63%), vigilance at street protests (51%), and airports and borders (46%).

Barriers facing Arabs in the workplace

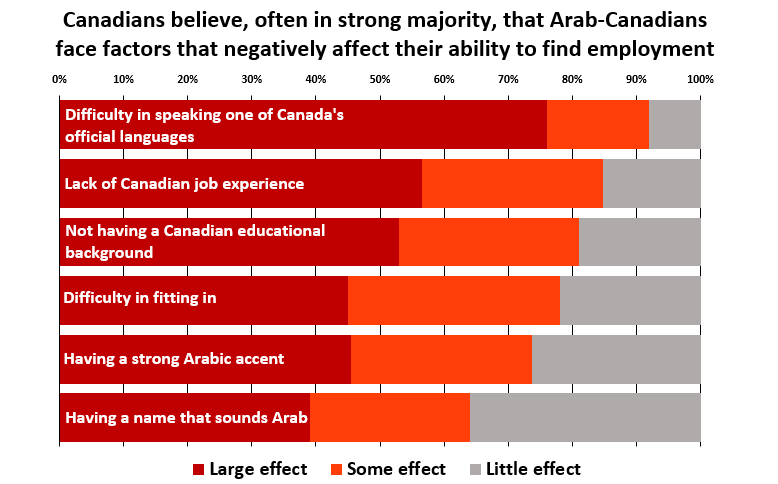

Canadians are also willing to acknowledge that many factors could negatively affect the ability of Arab-Canadians to secure employment. When asked about why Arab-Canadians face a joblessness rate 50% higher than the average, 92% of Canadians suggested that difficulty speaking one of Canada’s official languages could have a negative effect. Additionally, 84% said that lack of Canadian job experience was another important factor, followed by (81%) not having a Canadian educational background. Canadians felt that “difficulty in fitting in,” (78%), “having a strong Arabic accent” (73%) and “having a name that sounds Arab,” (64%) could also all have a negative effect on an Arab-Canadian’s job prospects.

View of Arabs as compared to other groups

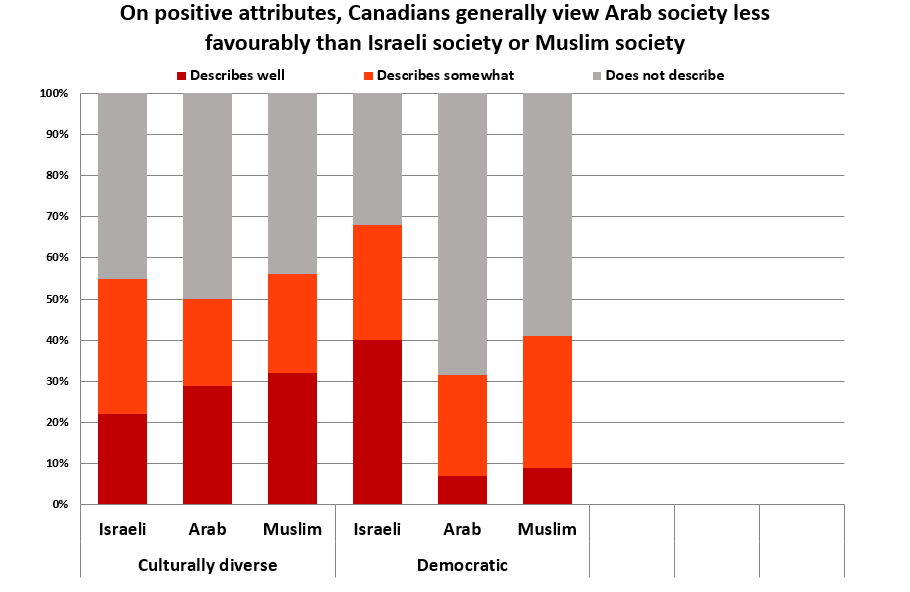

On eight different descriptors, the survey found that Canadians have a more negative view of Arab society as compared to Muslim society, and especially as compared to Israeli society. Even though the Arab world is incredibly diverse, with an ongoing legacy in art, science, politics and culture, Canadians repeatedly ranked Arab society lower than Muslim or Israeli society when it came to positive characteristics such as “culturally diverse” or “industrious.” Canadians’ views of Arab society on other descriptors – e.g. “anti-West” – are somewhat ironic, given that many Arab countries are led by regimes which act as proxies for Western countries, including the US and Canada, and do not represent their populations.

The two final questions in this survey deal with Canadian public opinion on Palestine and Israel, in part, because the cause of Palestine has always been a priority for many in the Arab-Canadian community.

In terms of the conflict between Israel and its neighbours, Canadians overall tend to hold Arabs much less responsible for prolonging the conflict, even when the question is phrased in a way that rhetorically benefits Israel. For example, only 48% say that Arab human rights violations against Israelis are a very significant factor in prolonging the conflict, compared to 73% who say that Israeli human rights violations against Arabs are very significant. Conservative voters are most likely than others to say that Arab actions are very significant in prolonging the conflict, while Liberal, NDP, and BQ supporters hold Israel far more responsible for the conflict. For example, 95% of NDP supporters said Israel’s “unwillingness to live in peace with Arabs” was significant in prolonging the conflict, followed by 75% Liberal, 62% BQ, and even a 51% majority of Conservative supporters.

Not only do Canadians consider Arabs less responsible in prolonging the Arab-Israeli conflict, but the final survey question indicates that they want Canada to take a pro-active, human rights-based approach to the conflict rather than a “both-sides” approach. Given the current lack of negotiations between Israel and the Palestinians:

- 77% of Canadians said that Canada should consistently condemn the human rights violations committed by either party;

- 61% say that Canada should encourage the International Criminal Court (ICC) to conduct investigations of alleged war crimes of all parties;

- 55% say that Canada should condition trade agreements upon each parties' respect for international law;

- Only 11% said that Canada should not get involved or speak out in any way, regardless of what happens.

This suggests that Canada’s approach to Israel and Palestine falls well short of what Canadians want to see from their government.

How familiarity with Arabs affects Canadians’ views

Finally, this survey also asked Canadians about their familiarity with Arabs (“don’t know any,” occasionally, regularly, socialize with or have Arab friends), and looked at these responses next to other answers. Not surprisingly, responses show that Canadians’ day-to-day familiarity with Arab-Canadians very much influences their attitudes toward Arabs on many issues. For example, the more contact that Canadians have with Arabs:

- The more open they are to immigration from Arab countries. 49% of Canadians who don’t know any Arabs feel there are too many Arab immigrants, compared to only 23% of Canadians who socialize with or have Arab friends.

- The more likely they are to have enhanced perceptions of positive stereotypes of Arabs, and diminished perceptions of negative stereotypes.

- The more likely they are to say that prejudice against Arab people is a “very serious problem” (42%).

- The more likely they are to oppose racial profiling.

- The less likely they are to place the blame on Arabs for prolonging the “Arab-Israeli conflict.”

This report will conclude with a section on the implications of the survey findings for public policy, and how governments and institutions can begin to address long-standing systemic problems of anti-Arab racism.

1. Survey Methodology

EKOS Research Associates (EKOS),[1] an experienced public opinion research firm, was hired to conduct an online poll to better understand Canadians’ perceptions of Arabs in Canada. Between May 26-31, 2021, a random sample of 1,005 Canadian adults from EKOS’ online panel, Probit, aged 18 and over, completed the online survey. The survey was made available to all respondents in either English or French. The margin of error associated with the sample is plus or minus 3.0 percentage points, 19 times out of 20. The margin of error increases when the results are sub-divided.

EKOS statistically weighted all the data by age, gender, education and region to ensure the sample’s composition reflects that of the actual population of Canada, based on 2016 census data. It is important to note that survey results were also cross-tabulated by these same demographic categories. Readers interested in the detailed breakdowns by demographic cross-section may consult the detailed survey results found at https://www.cjpme.org/survey2021.

The survey results presented in this report exclude residuals (“don’t know” and “no response”). Again, the full data set, both with and without residuals can be found at cjpme.org/survey2021. For most questions, fewer than 10% of respondents either did not reply or checked “don’t know,” and in most cases, far fewer than 10% did so. As such, residuals do not substantially affect the overall results. Where residuals are notably higher, this is noted in the report.

Given that Arab-Canadians are very likely to be misunderstood by the general public, public opinion polling presents a challenge. The responses to the questions in this survey are based on the perception of the respondents, not necessarily reality, and may be influenced by negative stereotypes or misinformation. To help make sense of this problem, the respondents to this survey were also asked about their familiarity with Arabs. Only 10% said that “I don’t think I know any Arabs,” while 48% said “I occasionally come across Arabs in day-to-day life (e.g. grocery store, gas stations, etc).” With a majority of respondents claiming to only come across Arabs occasionally or less, we can expect that many of the responses are not necessarily well informed.

Despite these challenges, the survey helps us to understand how the Canadian public views Arab-Canadians and the racism that they face. Towards that end the responses are relevant regardless of whether they are informed. Despite the limitations of this data, this survey shines light on a subject matter than is rarely researched and little understood.

As a final note, some of the questions in this survey deal with Canadian public opinion on Palestine and Israel. There are a few reasons for this. For many decades the issue had been presented by media and politicians as an “Arab-Israeli conflict,” and for many Canadians, Palestinians have come to represent the stereotypical image of Arabs, associated with negative stereotypes of violence and extremism. Often these anti-Arab stereotypes are counterposed with positive stereotypes about Israel, despite its own settler-colonial character. In addition, the cause of Palestine has always been a priority for many in the Arab-Canadian community, and has played a central role in Arab-Canadian organizing since the community first became politically involved in the 1940s.[2] How Canadians think about Palestine is therefore closely related to how they think about Arabs, and Arab-Canadians, in general.

1.1. Important Contextual Considerations

Shortly before the survey was conducted in late May 2021, there was a major escalation of violence in Palestine and Israel. Additionally, since mid-2020, there has been increasing awareness and activism regarding anti-Black and anti-Asian racism in Canada. Given that the survey touches on perceptions of developments in Palestine and Israel, people of Middle Eastern and North African origin, and the nature of discrimination against minority groups in Canada, either of these contextual factors may have had an impact on the answers of survey respondents. Additionally, since one of the groups we compare perception of Arabs to are East Asian, it is important to note that in 2020-2021 there has been a significant increase in hate crimes against Canadians of East Asian background, and this too may have influenced the results.[3]

Also of note is that the survey was conducted during a major drop in immigration levels in 2020, associated with travel restrictions due to the COVID-19 pandemic. This may have influenced how respondents viewed Canada’s the appropriateness of immigration levels.

2. Background: Arabs in Canada

Anti-Arab racism in Canada is an understudied problem, which is often conflated or subsumed under the topic of Islamophobia or anti-Muslim racism. However, Arab-Canadians are not synonymous with Muslim Canadians, and the Arab-Canadian population is quite diverse, requiring a separate examination.

There are almost 1 million Arab-Canadians (947,820) according to the 2016 census, as analyzed by the Canadian Arab Institute (CAI), [4] largely residing in Quebec and Ontario. This is a major increase in the population of about 75% since the 2006 census.[5] The most prevalent origins are from Lebanon, Morocco, Egypt, and Syria, in addition to another dozen countries across North Africa and the Middle East. Of those who were born in an Arab country, over half came to Canada as economic immigrants, and about one quarter as refugees.[6]

Arabs have been part of Canadian society since the 1880s (see below), but most of the population is relatively new to the country. Nearly two-thirds (61%) of Arab-Canadians are first generation immigrants, while another third (32%) are second generation, and only a small minority (7%) are third generation.[7]

The Arab-Canadian population is not defined by the ability to speak Arabic. A total of 629,055 people in Canada have knowledge of the Arabic language – representing about two-thirds of the entire Canadian population who are of Arab ethnic origin – while only 223,540 say it is the language most spoken at home.[8]

Although not all Arabs would be considered part of a “visible minority,” Arab-Canadians can nevertheless be understood as a racialized community, and the hatred and discrimination that they face can be understood in terms of “anti-Arab racism.” Without devising a simple, all-encompassing definition, Steven Salaita uses this term generally to describe a number of practices, including:

Acts of physical violence against Arabs based not on chance but largely (or exclusively) on the ethnicity of the victim; moments of ethnic discrimination in schools, civil institutions, and the workplace; the Othering of Arabs based on essentialized or biologically determined ideology; the totalization and dehumanization of Arabs by continually referring to them as terrorists … the taunting of Arabs with epithets … the profiling of Arabs based on name, religion, or origin; and the elimination of civil liberties based on distrust of the entire group rather than on the individuals within that group who may merit suspicion.[9]

Anti-Arab racism has been promoted by Canadian government policy (e.g. by racial profiling in national security measures), and it can be revealed in the inequality in employment and income levels faced by Arab-Canadians in comparison to the general population. Individuals may also be subjected to stereotypes and assumptions simply based on having “Arab” sounding names, or for otherwise being perceived as Arab (including the assumption that one might be a recent immigrant, even if they are a second or third generation Canadian).

Arab-Canadians may be automatically perceived to be Muslim, even though many are in fact Christian – as of 2006, only 44% of Arab-Canadians reported being Muslim, and another 44% belonged to a Christian group.[10] Perhaps for this reason, anti-Arab racism today tends to have an anti-Muslim or Islamophobic character. This has changed over time, as Houda Asal explains: for most of the 20th century, Arabs had an “intermediate position” within Canada’s racial hierarchy of immigrants – “unwanted” compared to Anglo-Saxons, but more desirable than those racialized groups most subordinated and targeted with discrimination.[11] After 1980, Arabs and Muslims have increasingly become the “target of choice” for racists,[12] with the rise in prominence of Islamophobia and the religious stereotype of the “violent, backward, fundamentalist Muslim.”[13] This group targeted by Islamophobia has “increasingly blurry boundaries,” and depending on the context Islamophobia could be used to target Arabs, East Asians, Afghans, Sikhs, and many other groups.[14]

3. Survey Results

3.1. Opposition to Immigration from Arab countries

The first Arabs to immigrate to Canada came from Lebanon (which was then part of Greater Syria) as early as the 1880s, and immigration from Arab countries has progressively increased starting after 1946.[15] The Arab-Canadian population has increased substantially over the last 15 years, from under 500,000 in 2006 to just under 1 million in 2016,[16] much of this due to immigration, and with a notable wave of more than 73,000 Syrian refugees after 2015, who were fleeing civil war.[17]

Public opinion about overall levels of immigration to Canada has remained relatively consistent over the past two decades. Polling from EKOS since 2005 shows that around half of Canadians continue to believe the right number of immigrants are coming to Canada, shifting slightly from 52% in 2005, to 44% in 2014, to 57% in 2020. Those who say there are “too many” immigrants fall between one quarter and one-third, from 25% in 2005 to 29% in 2014, with a recent dip to 14% in 2020.[18]

However, Canadians are less open to immigration depending on where those immigrants are coming from. While we are unaware of previous polling about immigration from Arab countries, a series of polls in 2019 found that almost one-third (30%) of Canadians say there are too many immigrants who are “members of visible minorities,”[19] and 57% of Canadians say that Canada should not be accepting more refugees.[20] A certain degree of this anti-immigration sentiment is likely a reaction to the wave of refugees from Syria after 2015,[21] and may reflect specifically anti-Arab racism.

3.1.2. Detailed Survey Findings

Canadians were asked about immigration, with one half of the survey respondents asked about immigration in general, and the other half asked about immigration from Arab countries in particular:

Split 1: In your opinion do you feel that there are too few, too many or about the right number of immigrants coming to Canada?

Split 2: Forgetting about the overall number of immigrants coming to Canada, of those who come would you say there are too few, too many or the right number who are from Arab countries?

Canadians are less supportive of the idea of immigration from Arab countries, compared to immigration in general. When asked about the number of immigrants in general, 45% said that the number was about right, and 28% said that there were too many. This is consistent with polling by EKOS over the past two decades.

When asked about immigration from Arab countries, 46% said the number was about right, but 38% said there were too many. Thus, Canadians were 10% more likely to say there are too many Arab immigrants, compared to immigrants in general. This suggests that anti-Arab prejudice may be a factor in how some Canadians think about immigration from Arab countries.

These numbers differ greatly when viewed by political party support. Liberal supporters were most likely to say that immigration was just right, both in general (60%) and from Arab countries (58%). Conservative Party supporters were most likely to say that there were too many immigrants (42%, compared to only 9% of Liberal and 11% of NDP supporters), and a significant majority of Conservative Party supporters said there were too many from Arab countries (68%, compared to 24% of Liberal and 21% of NDP supporters). NDP supporters were most likely to say there were too few immigrants in general (44%), as well as from Arab countries (35%). In summary, within every party there is less support for immigrants from Arab countries than for immigrants in general, and this is dramatically the case among Conservative Party supporters.

One unknown about this question is what survey participants had in mind when they responded that there were “too many” immigrants/Arab immigrants. Such a response could be driven by a variety of concerns, many of them likely reactionary or racist in nature, e.g. fear that immigrants are “taking too many jobs,” “living off welfare,” or fear that immigrants are negatively impacting the “fabric of Canadian society.”[22]

Respondents who say they “socialize with /have Arab friends” were most likely to say there is about the right amount (53%) of immigrants from Arab countries, and they were the least likely to say there were too many (23%). Respondents who said they “don’t know any” Arabs were most likely to say there are too many Arab immigrants (49%), and were the least likely to say there are too few (4%). Evidently, one’s level of day-to-day contact with Arabs has an impact on whether one views Arab immigration to Canada favourably.

Note: Thirty percent of the respondents who were asked their opinion about immigration from Arab countries replied “Don’t Know” or “No Response.”

3.2. Stereotypes about Arabs

3.2.1. Perceptions of Arabs and Arab-Canadians

As noted above, the Arab community in Canada is very diverse. Nonetheless, Arab-Canadians are often conflated with Muslim Canadians, and face both anti-Arab racism and Islamophobia in the form of stereotypes. It should be noted that just as Arabs can be perceived as Muslim, non-Arabs (for example Sikhs or Latin Americans) may also be mistakenly perceived to be Arabs if they share physical characteristics to the stereotypical depiction of Arabs in mainstream media (e.g. if they wear turbans, head coverings or eastern-style clothing, or have dark features or beards).

While Arab and Muslim stereotypes have been prominent in popular culture for many decades (e.g. the movie Aladdin), negative depictions of Arabs and Muslims have proliferated in the post-9/11 era, in part fueled by Western military intervention in the Middle East and the extensive promotion by governments of racial profiling. Law Professor Reem Bahdi has studied a series of “prevailing” stereotypes that are often used against both Arabs and Muslims, and that are commonly found even within Canada’s legal system. These include:

the conviction that Arabs and Muslims have a culturally ordained propensity towards violence (the “terrorist/inevitable violence theme”); the belief, regardless of their citizenship status, that Arabs and Muslims remain foreigners who threaten Western values (the “un Canadian/existential threat theme”); and the notion that Arabs and Muslims are dishonest (the “liar/untrustworthy theme”).[23]

These dehumanizing beliefs, including associated stereotypes such as Arabs are ‘oppressive towards women,’ have become features in the War on Terror, as they provide a justification for war and invasion abroad, and for repression at home.[24]

A survey in 2018 confirmed that Canadians hold many negative stereotypes towards Muslims, who were consistently perceived more negatively than Christians or Jews.[25] The present survey extends this analysis to Arabs, looking at how Canadians view Arabs in comparison to other ethnic groups, based on the same criteria.

3.2.2. Detailed Survey Findings

This question sought to determine whether Canadians held positive or negative stereotypes about the personal attributes of Arab-Canadians, compared to people of other ethnic groups. Respondents were divided into three groups and asked to rate their impressions of one of three different ethnic groups in Canada: Arabs, East Asians, and Europeans.[26] For each group, respondents were given 12 different words and phrases – 6 generally positive descriptors, and 6 generally negative ones – and asked their opinion on how well each word or phrase described that ethnic group. The order of the words/phrases was randomized. The wording and design of this question parallels a 2018 survey question[27] which evaluated the same impressions towards Christians, Jews and Muslims.

The question was as follows:

Using a scale of 1 to 5, where 1 means 'does not describe at all' and 5 means 'describes completely', please rate how well the following words or phrases best describes your impression of people of [Arab/East Asian/European] descent in Canada?

The words/ phrases were:

- Tolerant

- Adaptable

- Honest

- Hard-working

- Open-minded

- Contributes to the community

- Violent

- Fanatic

- Oppressive of women

- Set in their ways

- Poorly educated

- Keeps to themselves

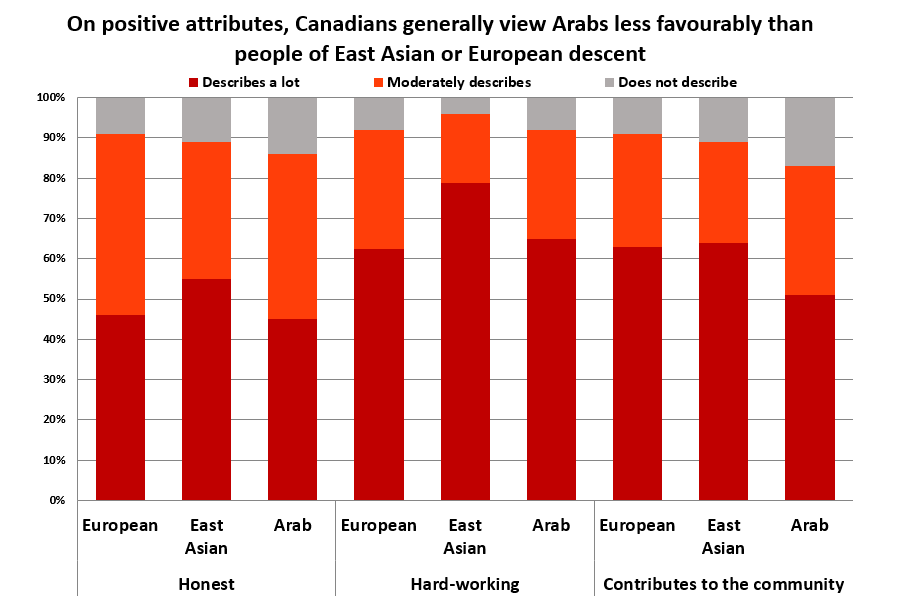

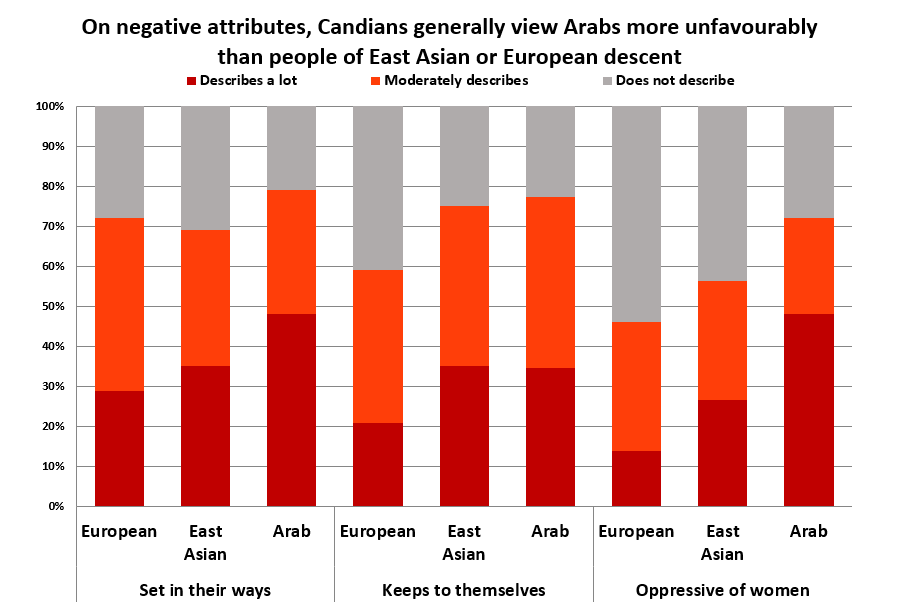

Across the board, the findings show that Canadians perceive Arabs more negatively than East Asians or Europeans. In virtually every category, Arabs rated lower on positive stereotypes, and higher on negative stereotypes. Compared to East Asians and Europeans, Arabs were much less likely to be perceived as tolerant, adaptable, open-minded, or as contributing to the community. At the same time, Arabs were more likely to be perceived negatively, such as violent or fanatic. Notably, 48% of Canadians said that the term “oppressive of women” describes Arabs a lot, compared to 27% for East Asians and 14% for Europeans. Similarly, 48% of Canadians said that the term “set in their ways” describes Arabs a lot, compared to 35% for East Asians and 29% for Europeans.

Arabs were not always singled out for negative attention. In some categories, such as “honest,” and “hardworking,” Arabs were ranked comparably to Europeans, while East Asians had the most favourable rating. While Arabs sometimes shared a negative ranking with another group, in no category did Arabs enjoy a clearly more favourable perception than both other groups.

Conservative and BQ supporters had the least positive impression of Arabs, while NDP supporters ranked Arabs most positively. For example, 61% of Conservative and 54% of BQ supporters said that the term “tolerant” does not describe Arabs, versus Liberal (25%), and NDP (15%). Similarly, 66% of Conservative and 44% of BQ supporters said that the term “open-minded” does not describe Arabs, vs. Liberal (27%), and NDP (18%) supporters.

With the exception of the NDP, supporters of the other parties expressed belief that the term “oppressive of women” described Arabs a lot: 73% of Conservative supporters, 46% of BQ, and 43% of Liberal, compared to 26% of NDP supporters. Similarly, supporters across most parties said that the term “set in their ways” described Arabs a lot: Conservatives (74%), BQ (78%), Liberal (43%), and NDP (25%).

Comparing these results with the 2018 survey on Islamophobia,[28] it is clear that Arabs suffer from many of the same negative perceptions as Muslims. This may be a result of the common conflation between Arabs and Muslims, and the inability to distinguish between the two groups. Fifteen percent of Canadians said that the category “violent” describes Arabs a lot, compared to 14% of Canadians who said the same about Muslims, while 48% of Canadians said that “oppressive of women” describes Arabs a lot, compared to 45% of Canadians who said the same about Muslims.[29]

Respondents who know or socialize with Arabs tend to view them more positively and are less likely to subscribe to negative stereotypes. Respondents who claim to “socialize with /have Arab friends” were the most likely to say that “violent” does not describe Arabs (70%), while respondents who “don’t know any” Arabs were the most likely to say that “violent” describes Arabs “somewhat” (48%) or completely (12%).

Note: Between 6%-14% of respondents replied “Don’t know” or “No response” to this series of questions.

3.3. Perception of Prejudice Against Arabs in Canada

3.3.1. Prejudice against Arabs in Canada

Like other racialized communities, Arab-Canadians face significant racial prejudice and even violence, although it is unclear how these levels of prejudice and violence compare to that faced by other communities.[30]

In 2020, during the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic, Canada saw a 37% increase in police reported hate crimes, with “hate crimes targeted race or ethnicity” almost doubling to 1,594 incidents from 884 in 2019. This increase is largely due to a 92% increase in crimes targeting the Black population (663 incidents total), and a 301% rise in incidents against the East or Southeast Asian population (269 incidents).[31]

Comparatively, hate crimes targeting Arabs or West Asians stayed roughly the same as the previous year, at 123 incidents or 5% of the total. [32] Nonetheless, a July 2020 study found that 12.5% of Arabs perceive there to have been an increase in incidents of harassment or attacks based on race, ethnicity, or skin colour since the start of the pandemic, slightly more than noted by Black respondents (12%) but much lower than Chinese (30.4%) or Korean (27%) respondents.[33]

It has to be kept in mind that these numbers only consider incidents reported to the police, whereas actual incidents may be much higher. Racialized communities are less likely to report hate crimes for a number of reasons, including the fear of further victimization or a lack of trust in the criminal justice system.[34] Another contributing factor for under-reporting is that unlike other communities, the Arab community does not have a centralized community-based method to report racist incidents – especially those that are not necessarily criminal in nature. As a result, the official numbers almost certainly underestimate the actual level of anti-Arab hostility. This is the case in the US, where the mistrust and fear of Arab Americans towards the police, in part due to being racially profiled by national security programs, contributes to underreporting.[35] Making things worse, this lack of data results in a misunderstanding of the scope of the problem, leading to the under-resourcing of these communities by governments.

Apart from outright hate crimes, Arab-Canadians (and those perceived to be Arabs) have often been targeted with both anti-Arab and anti-Muslim sentiments, often interchangeably. An example from 2021, in which Arab-Canadian cabinet minister Omar Alghabra was smeared by a political opponent with Islamophobic innuendo for having led a secular Arab organization,[36] illustrates the way that anti-Muslim discourses can be directed against Arabs, regardless of their religion. In a similar manner, both Arabs and Muslims have faced Islamophobia and hostility following 9/11 and with the rise of the War on Terror, including racial profiling and other discriminatory policies. Scholars argue that anti-Arab racism perpetuated by the Canadian state, whether through national security policies or through legislation like Québec’s Bill 21[37] or the federal “Zero Tolerance for Barbaric Cultural Practices Act,”[38] filters down and makes racism more common and normalized among the general public.[39]

3.3.2. Detailed Survey Findings

Canadians were asked about whether they think that prejudice against Arabs is a problem, compared to prejudice against minority groups in general. Respondents were divided into two groups and asked one of two related questions:

- In your opinion, how serious a problem is prejudice against minority groups in Canada? (e.g. Black, Arab, Jewish, Indigenous, Asian, etc.)

- In your opinion, how serious a problem is prejudice against Arab people in Canada?

Respondents were given a scale of 1 to 5, with 1 being “not a problem at all” and 5 being a “very serious problem.”

When asked about prejudice against minority groups, a majority (56%) of respondents said that it was a serious problem (4 or 5 on a scale of 5), 27% said it was somewhat of a problem (3 on a scale of 5), and 17% said that it was not a problem (1 or 2 on a scale of 5). Similarly, when asked about prejudice against Arab people, a slightly smaller majority (53%) said it was a serious problem, 26% said it was somewhat of a problem, and 21% said that it was not a problem.

In sum, an overwhelming 83% of respondents consider prejudice against minority groups overall to be a problem, while 79% consider prejudice against Arabs in Canada to be a problem.

When broken down by political party the issue is more polarizing. Conservative and BQ supporters are the most likely to downplay the issue of prejudice across the board. Nearly a third (30%) of Conservative and 22% of BQ supporters said that prejudice against minority groups was not a problem, compared to 6% of Liberals and 6% of NDP. When asked specifically about Arabs, over a third (36%) of Conservatives said that prejudice was not a problem, compared to 16% of Liberals, 8% of NDP, and 13% of BQ.

Liberal (70%) and NDP (68%) supporters were the most likely to say that prejudice in general is a serious problem, vs. 38% of Conservatives, and 24% of BQ. Only NDP and BQ supporters saw prejudice against Arabs as being more serious than prejudice in general. When NDP voters were asked about prejudice against Arabs in particular, 80% said it was a serious problem, while 12% said it was somewhat of a problem, compared to 54% and 33% for BQ supporters, 56% and 28% for Liberal supporters, and 33% and 31% for Conservative supporters.

The results are similar to a 2020 EKOS poll[40] which found that 59% of Canadians said that prejudice against minority groups was a serious problem (compared to 56% in this poll). In that survey, 35% of Canadians said that prejudice against Jewish people was a serious problem and 28% said that it was a somewhat of a problem. Canadians are nearly 20% more likely to see prejudice against Arabs as a serious problem, compared to prejudice against Jewish people.[41]

Respondents who claimed to “socialize with /have Arab friends” were by far the most likely to indicate that prejudice against Arab people is a “very serious problem” (42%).

3.4. Attitude Towards Racial Profiling of Arabs by Security Institutions

3.4.1. Security Measures and Discrimination Against Arabs in Canada

Arab-Canadians are subject to racial profiling in Canada similar to that experienced by other racialized groups. A study of Montreal police data between 2014 and 2017 found that the number of street checks of Arabs amounted to 7.9% of the city’s entire Arab population, making Arabs the third most targeted group after Black (16.5%) and Indigenous (17.9%) peoples. It concluded that “young Arab people between the ages of 15 and 24 were four times more likely than white people of the same age to be targeted for a street check.”[42] In Ottawa, a police report found that “Middle Eastern” drivers were the group most likely to be stopped by police, when accounting for their share of the population.[43]

There are other forms of racial profiling that target Arabs more specifically. In the early days of the so-called “War on Terror” immediately following 9/11, Arab and Muslim communities in Canada faced racial profiling in the rollout of enhanced security surveillance measures. For example, some of the measures which incorporated an aspect of racial profiling included extra-territorial rendition to be tortured, over-surveillance, screening at airports, the freezing of assets, and having names shared with foreign security agencies.[44]

Arabs are often perceived as Muslim, and subjected to Islamophobia and anti-Muslim discrimination. Consequently, they may be affected by the expansion of national security powers, which have a “disproportionate impact” on Muslim communities.[45] For example, this includes security legislation such as Bill C-24 (which allowed Canada to strip people of citizenship on grounds of national security), and Bill C-51 (which increased surveillance powers for “anti-terrorism” purposes).[46]

Arabs and Muslims have also reported racial profiling connected to support (or perceived support) for Palestinian human rights, a cause which is often viewed with prejudice and conflated with support for terrorism. An Ontario Human Rights Commission study in 2017 found that Muslim and Arab respondents believed they experienced racial profiling based on activities in support of Palestinians, and reported being questioned by CSIS, being accused of supporting terrorism, or being punished (or threatened) by their employers because of this support.[47] In a similar way, in 2021, two separate reports concluded that the Canadian Revenue Agency is discriminating against Muslim charities in its auditing and “risk-assessment” processes, based on prejudices and stereotypes about support for terrorism – often related to support for Palestinians.[48] In May 2021, police responded to pro-Palestine rallies across the country by arresting, intimidating or fining protestors, leading many to openly question if they were being specifically targeted for their political beliefs.[49]

3.4.2. Detailed Survey Findings

Respondents were asked if they would support a variety of increased security measures targeting Arabs. Respondents were divided into three groups and asked one of three questions: Would they support or oppose the increased security measure in general, if it targeted Arabs, or if it targeted East Asians.[50] The question was as follows:

Canadian security organizations deal with potential threats from a number of different sources. In order to deal with these threats, how much would you support or oppose….

- Increasing security scrutiny on visa applications [of Arabs / of East Asians / (blank)]

- Increasing security screening [of Arabs / of East Asians / (blank)] at airports and border crossings

- Allowing police to stop and question [Arabs / East Asians / people] in the street

- Being especially vigilant with street protests or demonstrations [organized by Arabs / organized by East Asians / (blank)]

- Giving greater scrutiny to the finances of [Arab / East Asian / (blank)] civic organizations

Respondents were given a scale of 1 to 5, with 1 being “strongly oppose” and 5 being “strongly support.”

The results suggest that Canadians are concerned about security, but somewhat uncomfortable with racial profiling. In every instance, Canadians are more likely to oppose increased security measures if they target specific ethnic groups. Conversely, Canadians are also more likely to support these measures when they are targeted at a general population.

For example, a small majority of Canadians (54%) support increasing airport and border security in general, but oppose these measures when the question targets Arabs (53%) or East Asians (55%) in particular. Similarly, Canadians are divided over whether to be vigilant about street protests in general, with 37% in support and 36% in opposition, but a majority are opposed to increased vigilance against protests organized specifically by Arabs (54%) or East Asians (52%).

Conservative and BQ supporters were much more likely to support increased racial profiling. Conservatives support targeting Arabs with greater scrutiny when it comes to visa applications (71%), finances of civic organizations (63%), vigilance at street protests (51%), and airports and borders (46%). BQ supporters are in support of targeting Arabs when it comes to scrutinizing the finances of civic organizations (71%), vigilance at street protests (68%), visa applications (60%), and airports and borders (43%).

Some results were strongly correlated to the respondents’ personal familiarity with Arabs. In the most striking example, 76% of those who claimed to “socialize with /have Arab friends” were opposed to increasing security scrutiny on visa applications of Arabs, while the same proposal was supported by 65% of those who said they “don’t know any” Arabs.

Note: “Don’t know” and “No response” replies to this series of questions were between 2%-10%, and only a few points higher for the question on ‘civic organizations.’ In many cases the “neither” category was also quite large.

3.5. Discrimination in Employment Opportunities for Arab-Canadians

3.5.1. Employment Challenges Faced by Arabs in Canada

The Arab-Canadian population has a significantly higher unemployment rate, and a lower total income, than the Canadian population as a whole. A report by the Canadian Arab Institute (CAI),[51] based on 2016 census data, found that the Arab visible minority population had an unemployment rate of 13.5%, much higher than both the total visible minority population (9.2%) and the Canadian population at large (7.7%). Arab-Canadians also had an average total income of $33,542 compared to $47,487 for the Canadian population as a whole. This is despite the fact that the Arab population has higher levels of education than the general population.[52] CAI executive director Shireen Salti has suggested that this discrepancy may be a result of discrimination, as well as employers refusing to recognize the credentials that immigrants to Canada received in another country.[53]

The high unemployment rate is reflected in higher poverty rates and lower financial security for Arabs in Canada. Twenty-eight percent of Arab-Canadians were living in poverty prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, compared to 9.6% of White respondents.[54] In May-June 2020, 44% of Arabs reported a strong or moderate impact of COVID-19 on their ability to meet financial obligations or essential needs, which is almost double the impact reported by White respondents (23.2%).[55]

These economic differentials suggest that anti-Arab racism in Canadian society is a significant factor for Arabs’ lower socio-economic status in Canada. And Arabs in Canada also believe their identity can have a detrimental impact on the job and career prospects. University of Windsor Law Professor Reem Bahdi writes that 27% of Arab-Canadians in Ontario have tried to hide their Arab identities, according to a 2018 survey. One respondent in Bahdi’s survey explained that they did it because: “it is clear to me that racism exists against Arabs and open membership can negatively affect me in the hunt for jobs.”[56]

Within the Arab community, stories relating to the phenomenon that Bahdi describes are rampant. Members of racialized groups sometimes talk about “whitening” their CVs/resumés when applying for jobs.[57] Arab-Canadians are known to “whiten” CVs/resumés by doing some of the following:

- Changing an Arab-sounding name to something more “Canadian-sounding,” e.g. changing Mohammed to Moe;

- Not mentioning the fact that they speak Arabic;

- Removing reference to involvement in Arab or ethnic campus/community groups;

- Listing “Canadian-sounding” interests, e.g. hockey, skiing.

3.5.2. Detailed Survey Findings

Canadians were asked about which factors might negatively impact the ability of Arab-Canadians to find employment. The preamble of the question provided the factual context that a problem does exist, and Canadians were asked to identify which factors may play a role.

The question read:

Statistics Canada has found that joblessness among Arab-Canadians is almost 50% higher than the Canadian average. Please rate how strongly you think the following factors could negatively affect the ability of Arab-Canadians to find employment in general:

- Difficulty in speaking one of Canada’s official languages

- Difficulty in fitting in

- Having a name that sounds Arab

- Not having a Canadian educational background

- Lack of Canadian job experience

- Having a strong Arabic accent

Respondents were given a scale of 1 to 5, with 1 being “No negative effect” and 5 being “Very large negative effect.” The order of the potential factors affecting employment was randomized.

This question sought to assess the degree of racism that Arabs might face in the Canadian employment market. Respondents were asked to predict how much certain attributes might hypothetically influence a candidate’s ability to find employment.

While respondents’ perception of the impact of certain job candidate attributes is not a true measure of the actual impact, it hopefully serves as a rough proxy for the degree of impact. For example, if respondents say that “having a name that sounds Arab” might have a large negative impact on someone’s ability to find a job – whether from experience or from conjecture – it probably does, in reality, have a large negative impact.

The survey designers sought to create a list of attributes which: 1) would be examples of discriminatory practice in most situations; 2) would be applicable to a large percentage of Arab candidates; 3) would be brief and easy for respondents to understand; and 4) would not be a material obstacle to the candidate’s ultimate job effectiveness. For example, evaluating a job candidate for “having a strong Arabic accent” would be clearly discriminatory, it is true of many first-generation Arab immigrants, it is easy for survey respondents to understand, and it would not typically have a material impact on the candidate’s ability to perform his job.

Note that the factors listed above (difficulty speaking English or French, lack of Canadian educational or job experience) tend to describe primarily first-generation Arab-Canadians. But in fact, 2 out of 5 Arab-Canadians were born right here in Canada. They have no difficulty speaking English or French and their educational and job experience is Canadian. It is remarkable, therefore, that so many Canadians still feel that these factors have a large effect – and suggests that Canadians tend to assume that their fellow Arab-Canadians are primarily recent immigrants.

A large majority of Canadians (76%) believed that difficulty speaking one of Canada’s official languages would have a “large negative” effect (4 or 5 on a scale of 5) on the ability of Arab-Canadians to find employment. A small majority also believed that a lack of Canadian job experience (56%), or not having a Canadian educational background (53%) could have a “large negative” effect.

In addition to such factors based on credentials or qualifications, respondents indicated that Arab-identifiers or characteristics may also play a role. For example, 45% said that “difficulty fitting in” could have a “large negative” effect on the ability of Arab-Canadians to find employment. Forty-five percent said that “having a strong Arabic accent” and 39% said that “having a name that sounds Arab” could have a “large negative” effect.

Taken together with those who indicated “some negative effect” (3 on a scale of 5), an overwhelming 92% of Canadians believe that difficulty speaking one of Canada’s official languages creates some, a large, or a very large negative effect on an Arab-Canadian’s job prospects. Similarly, a majority of Canadians believe that employment prospects are negatively impacted by: a lack of Canadian job experience (84%); not having a Canadian educational background (81%); and more disturbingly, having “difficulty in fitting in” (78%); having a strong Arabic accent (73%); and having a name that sounds Arab (64%).

Once again, the results were polarized by party support. Conservatives were most likely to say that having an Arab sounding name would have little effect on employment (41%), while 30% said some effect and 29% said large effect. Conversely, most NDP supporters (55%) said it would have a large effect, while 17% said some effect and 29% said little effect. Similarly, Conservatives were less likely to say that an Arabic accent would have a large negative effect (39%), while most NDP supporters said that it would (53%).

In other words, whereas Conservative supporters were most likely to point to problems with credentials or qualifications as an explanation for joblessness, NDP supporters were most likely to suggest that employers may be discriminating against applicants on the basis of their Arab identity.

Respondents who said they “don’t know any” Arabs were most likely to say that “difficulty speaking in one of Canada’s official languages” or “difficulty fitting in” would have a large negative effect, whereas respondents who claimed to “socialize with /have Arab friends” rated those hypothetical factors much lower. Those with greatest familiarity with Arabs were more likely than other respondents to say that “having a name that sounds Arab” would have a negative effect on employment.

While all racialized communities face similar challenges, it is encouraging that so many Canadians acknowledge that an Arab name, accent and culture may feasibly play a significant role in their ability to secure a job. For Arabs who are also Muslim, these challenges are sure to be even greater, as they may also face formal obstacles like Bill 21 in Quebec, or informal day-to-day prejudice in the job market, related to religious clothing like hijabs.

3.6. Perceptions of Arab Society

3.6.1. The Origins of Stereotypes about Arab Culture

As noted above, the Arab-Canadian community is incredibly diverse, as is the Arab world at large. The Middle East is cradle to some of the world’s most impressive ancient cultures, with an ongoing legacy in art, science, politics and culture. Nonetheless, stereotypes about Arab society as monolithic and backward are quite common, fueled by widespread media representation about Arabs which are overwhelmingly negative.[58]

Of course, there are reasons that certain negative notions about Arab society may abound. Canadians may consider the Arab world to be “anti-democratic” based in the fact that many Arab countries are governed by autocratic governments that do not represent their populations. Most Canadians, however, are not well informed about the history, culture or governments of the Arab world, and so it is possible that these common perceptions could be related to stereotypes about Arabs themselves.

Too often, stereotypes about Arab society (i.e. undemocratic or violent) are deployed in contrast with the perceived superiority of the state of Israel. In popular Canadian discourse, Israel is often depicted as a progressive and advanced society surrounded by barbaric Arab states, as a way to bolster support for pro-Israeli foreign and trade policy. As Prime Minister Stephen Harper told the Israeli Knesset in 2014, “Israel is the only country in the Middle East which has long anchored itself in the ideals of freedom, democracy and the rule of law,” and which is threatened beyond its borders by “those who scorn modernity, who loathe the liberty of others, and who hold the differences of peoples and cultures in contempt.”[59] Harper’s comments were ahistorical and racist, yet similar commentary often finds its way into the Canadian public discourse.[60] Furthermore, most authoritarian Arab regimes are themselves substantially supported by Western countries, including the US and Canada, as part of a continued legacy of imperialism and colonialism in the region.

3.6.2. Detailed Survey Findings

This question sought to determine whether Canadians held positive or negative stereotypes about Arab society, compared to people of other ethnic groups. Respondents were divided into three groups and asked to rate their impressions of one of three different societies: Arab, Israeli and Muslim.[61] For each group, respondents were given 8 different words and phrases[62] – 5 generally positive descriptors, and 3 generally negative ones – and asked their opinion on how well each word or phrase described that society. The order of the words/phrases was randomized.

The question read as follows:

Using a scale of 1 to 5, where 1 means 'does not describe at all' and 5 means 'describes completely', please rate how well the following words or phrases best describes your impression of [Arab/Israeli/Muslim] society?

- Culturally diverse

- Militaristic

- Industrious

- Democratic

- Innovative in art and science

- Conservative

- Anti-West

- Trend-setting

For each category, respondents were given a scale of 1 to 5, with 1 being “Does not describe at all” and 5 being “Describes very well.” Bullet order was randomized.

For phrases with more positive connotations, Canadians consistently ranked Arab society lower than Muslim or Israeli society, with the exception of “Innovative in art and science” for which Muslim society was ranked slightly lower. For example, a large majority of Canadians said that Arab society cannot be described as either “Democratic” (69%) or “Trend setting” (68%).

Israeli society was rated highest in terms of “Industrious,” “Innovative in Arts and Science,” “Trend-setting,” However, one third (32%) of respondents said that Israeli society cannot be described as democratic.

For characteristics with potentially negative connotations, the results are more mixed. A large majority of Canadians said that “Militaristic” describes Israeli society a lot (67%), vs. 44% for Arab society and 35% for Muslim society. On the other hand, Canadians were most likely to say that “Conservative” and “Anti-West” describes Arab and Muslim societies, although a majority also said that “Conservative” described Israeli society a lot.

Overall, Muslim society fared marginally better than Arab society, but usually well below Israeli society.

In terms of party support, the results follow a familiar trend in that Conservative Party supporters tended to have more negative perceptions of Arab society and more positive perceptions of Israeli society, while NDP and Liberal supporters demonstrated the opposite. For example, 85% of Conservative supporters said that “Democratic” does not describe Arab society, compared to 62% Liberal and 61% NDP. On the other hand, 57% of Conservatives said that “Democratic” describes Israeli society very well, compared to 32% Liberal and 37% NDP. Interestingly, around half of BQ (53%) and NDP (48%) supporters say that Israeli society cannot be described as democratic.

Note: “Don’t know” and “No response” replies to this series of questions were usually around 10-15%, but for Israeli society they rose to 15-25%.

3.7. Perceptions of Culpability in the Arab-Israeli Conflict

3.7.1. Israel, Palestine, and the “Arab-Israeli Conflict”

In mainstream media and popular culture, the issue of Israel and Palestine is often framed in the terms of a “conflict” between two generalized groups of people – Israelis and Arabs.

To an extent, there is a historical reason for this. When partition of historic Palestine was proposed and the state of Israel was established in 1948, neighboring Arab states were relatively united in opposition to Israeli colonization of Palestine. Today, many Arab states maintain borders with territories under Israeli occupation, and host Palestinian refugees. Israel continues to occupy the Syrian Golan Heights, and conducts military strikes in Syria and Lebanon.

The tendency to use an “Arab-Israeli” framework is likely to shape how the public views the issue. One implication is that it transforms the specific issue of Palestine into a “conflict” between two undifferentiated people groups. This may even unfairly influence the perceptions and stereotypes that people hold towards Arab and Jewish people, regardless of where they live or their connection to the region.

Similarly, while “conflict” is the most common term used to describe the political reality in Israel and Palestine, the term is itself quite misleading, as it evokes a situation between two equal and aggrieved parties. The reality of the situation, however, is not balanced. Instead, it is a deeply asymmetrical situation of an occupier and an occupied population.[63]

This false notion of equal sides can have negative policy implications. For example, the Canadian Government uses language which urges ‘both sides’ to restrain from violence or to avoid unliteral actions, contributing to a false sense of balance and allowing Canada-Israel bilateral relations to continue with business-as-usual.

The question here is whether this ‘both-sides’ approach aligns with the perception of the situation as held by Canadians, or if Canadians weigh the responsibility of the parties differently.

3.7.2. Detailed Survey Findings

Canadians were asked about their views on which side is responsible for prolonging the “Arab-Israeli Conflict.” Respondents were divided into two groups and asked to rate how significant they believed each of four factors to be in prolonging the conflict. Bullet order was randomized, but the alignment was kept the same, so that each respondent had two questions about Israelis and two about Arabs. No respondent was asked about the same statement for both Israelis and Arabs.

The question read as follows:

How significant do you believe each of the following factors are in terms of prolonging the Arab-Israeli Conflict:

- [Arab human rights violations against Israelis] / [Israeli human rights violations against Arabs]

- [Israelis’ desire to expand their borders] / [Arabs’ desire to expand their borders]

- [Arabs’ lack of interest in negotiating with the Israelis] / [Israelis’ lack of interest in negotiating with the Arabs]

- [Israelis’ unwillingness to live in peace with Arabs] / [Arabs’ unwillingness to live in peace with Israelis]

Respondents were given a scale of 1 to 5, with 1 being “Not at all significant” and 5 being “Extremely significant.”

Once again, it is important to note that this question gauges opinion on an “Arab-Israeli conflict,” which is not the terminology that the survey authors share, as explained above.

The question was also written to be as symmetrical and “balanced” as possible, with both Israelis and Arabs being accused of the same infractions. However, the reality of the situation is not balanced, as explained above. While the question was framed this way to avoid leading questions, the result of this false balancing is that it is effectively biased towards Israelis.

And yet, even in this framing which rhetorically benefits Israel, Canadians consistently place the responsibility for prolonging the conflict onto Israel:

- 73% say that Israeli human rights violations against Arabs are a very significant factor in prolonging the conflict, compared to 48% who say that Arab violations against Israelis are a very significant factor.

- 78% say that Israelis’ desire to expand their borders is very significant, vs 50% for Arabs.

- 73% say that Israelis’ lack of interest in negotiating with the Arabs is very significant, vs 56% for Arabs.

- 71% say that Israelis’ unwillingness to live in peace with Arabs is very significant, vs. 56% for Arabs.

Conservative supporters were more likely than those of other parties to say that Arab actions in the “conflict” were very significant, and less likely than supporters of other parties to say that Israeli actions were very significant. For example, 71% of Conservative supporters said that Arab human rights violations against Israelis were very significant, compared to 46% BQ, 38% Liberal, and 32% NDP. Even so, half of Conservative supporters (49%) said that Israeli human rights violations were very significant, compared to 84% Liberal and NDP, and 75% BQ supporters.

Canadians tend to be more critical of Israelis in terms of their intentions as well. When it comes to Israelis’ unwillingness to live in peace with Arabs, 95% NDP, 75% Liberal, 62% BQ, and 51% Conservative supporters said this is very significant. For Arabs’ unwillingness to live in peace with Israelis, 71% of Conservative supporters said it was very significant compared to 58% BQ, 49% Liberal, and 37% NDP supporters. Conservative supporters are the only ones to have a more favourable view of Israelis than Arabs, and BQ supporters are the only ones to have a similar opinion of both groups.

Respondents who say they “don’t know any” Arabs were far more likely than those with higher familiarity levels to say that Arab human rights violations against Israelis were very significant (68% of those who “don’t know any” Arabs, compared to 48% who “occasionally” meet Arabs,” 43% who “regularly” meet Arabs, and 42% who “socialize with /have Arab friends”). However, they were about as likely as the others to say that Israeli rights violations were also very significant (73% to 72%, 77%, and 75%, respectively). Similarly, those with the lowest familiarity with Arabs were far more likely to say that Arabs’ unwillingness to live in peace with Israelis was very significant (65%, compared to 47% for those who “socialize with /have Arab friends”), but had comparable answers on the question of Israeli unwillingness to live in peace with Arabs (78% very significant, compared to 72% with the highest familiarity). In other words, those with the lowest familiarity of Arabs were much more likely to be critical of the role of Arabs in the conflict, but they were just as critical of Israelis as anyone else.

These results suggest that Canada’s ‘both-sides’ approach is at odds with the views of Canadians, who clearly see Israel as bearing much greater responsibility for the ongoing conflict. This distinction is clear in the data, even when the question itself was designed in a way that was rhetorically biased towards Israel. Given these findings, one can expect that Canadians would support government policies which attempt to hold Israel accountable.

Note: “Don’t know” and “No response” replies to this series of questions were between 15%-20%. This is a higher residual rate than for most of the other questions, which may suggest that Canadians do not feel that they know enough about the issue to share an opinion.

3.8. Desired Role for Canada in Israel-Palestine Conflict

3.8.1. Canada’s Involvement in the Israel-Palestine Conflict

After more than fifty years of Israel’s occupation, the collapse of the Oslo “Peace Process” and the lack of negotiations between Israeli and Palestinian leaders, and the continued growth of Israeli settlements, many international law experts and human rights groups have concluded that a viable two-state solution is no longer possible. Despite this lack of progress, Canada has continued to advocate for an untenable two-state solution, while building close bilateral relations with Israel. Canada has not undertaken any efforts to pressure Israel to end the occupation, honour refugee rights, or adhere to international law. While Canada’s approach is often characterized as “balanced,” it is oriented towards maintaining the status quo – of which Israel, as occupying power and international scofflaw, is the beneficiary.

There are a few policy areas where Canada has room to take a more proactive approach towards the conflict, but has generally declined to do so:

- Under Stephen Harper, Canada eliminated funding to UNRWA, the United Nations (UN) agency for Palestine refugees. This was restored under Justin Trudeau, but funding has been maintained at inadequate levels despite the agency experiencing a severe financial crisis.

- For many years Canada has been slow to criticize Israeli human rights violations, using mild language, and always couching any criticism with an emphasis on Canada’s strong friendship with Israel. In contrast, Canada responds to violence from Palestinians with more forceful condemnation. Moreover, under both Harper and Trudeau, Canada has voted overwhelmingly against motions that are critical of Israel at the UN and other international bodies.

- Under Harper and Trudeau, Canada has strengthened and modernized multi-lateral agreements, including the Canada-Israel Free Trade Agreement (CIFTA). This has been a priority for the government despite Israel’s continued occupation and other human rights violations. CIFTA even extends preferential trade benefits to goods from illegal Israeli settlements, eliminating any incentive for Israel to curb settlement growth (and in contravention of UN Security Council resolution 2334).

- Under Harper and Trudeau, Canada has sought to discourage the International Criminal Court (ICC) from investigating alleged war crimes by Israeli and Palestinian officials, citing jurisdiction issues and condemning the move as a “unilateral action.”

Taken together, Canada’s actions protect the status quo and discourage initiatives which would hold Israel accountable for their occupation of Palestinian territory, for preventing the repatriation of refugees, and other human rights violations. This raises a question of whether Canada’s current ‘do nothing’ approach to Israel and Palestine has public support, or if Canadians are open to the government taking a more proactive approach to hold parties accountable.

3.8.2. Detailed Survey Findings

Canadians were asked their opinion on what approach Canada should take towards the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, given the absence of negotiations. The question read as follows:

Regarding the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, the Canadian government has long supported a negotiated settlement providing peace and security for all.

However, there have been no negotiations since 2014, and the UN warns of a deteriorating situation. Given the current status, which of the following approaches would make sense for Canada?:

- Canada should not get involved or speak out in any way, regardless of what happens

- Canada should provide more aid to the refugees from the conflict

- Canada should consistently condemn the human rights violations committed by any party

- Canada should condition trade agreements upon each parties’ respect for international law

- Canada should encourage the International Criminal Court to conduct investigations of alleged war crimes of all parties

Beside each option was a checkbox, and respondents were able to check as many as they wished. Option “a” was exclusive, so that if someone chose this option, they would not be able to check the other boxes. The bullets were variously ordered from either a-e, or e-a.

It is important to note that the results do not indicate absolute support or opposition to any specific bullet point, but may instead indicate relative preference.[64] Therefore, the policies should be interpreted in terms of their popularity relative to the other points.

The results suggest that, given a lack of negotiations, Canadians want their government to take a proactive human rights-oriented role towards Israel-Palestine. Of note, 77% of respondents said that Canada should consistently condemn the human rights violations committed by either party. Furthermore, a majority of respondents say that Canada should encourage the International Criminal Court (ICC) to conduct investigations of alleged war crimes of all parties (61%) and that Canada should condition trade agreements upon each party’s respect for international law (55%). Only 11% said that Canada should not get involved or speak out in any way, regardless of what happens.

Support for increasing aid to refugees from the conflict was relatively strong, at 41%. The Trudeau government currently gives $20-25 million per year for health and education services for Palestinian refugees, so 41% respondents’ support for additional funding is quite revealing. Respondents who did not support increasing aid to refugees may not be against it, per se, but may simply consider other Canadian interventions more important or effective.

Conservative supporters were more likely than those from other parties to support inaction (17%), and the least likely to support proactive measures. Nonetheless, almost three quarters (72%) said that Canada should be consistent in condemning human rights violations, and almost half said that Canada should support an ICC investigation (49%) or condition trade (47%). This is in stark contrast with the one-sided pro-Israel position that the party has taken for many years.

NDP supporters were most likely to support an ICC investigation (71%) and increased aid to refugees (62%), while BQ supporters were more likely to support conditioning trade (73%). A majority of Liberal supporters also supported condemning human rights violations (83%), an ICC investigation (62%), conditioning trade (56%), and increasing aid to refugees (54%).

Above all, Canadians want their government to pursue proactive measures to support human rights and international law, instead of Canada’s current approach of taking no action and only issuing mild criticism of Israeli policies and actions.

4. Survey Findings for Public Policy

The survey results confirm that anti-Arab views are very much present in Canadian society and these views are having an impact on the socio-economic well-being and political representation of Arab-Canadians today. Furthermore, the findings, which are similar to past studies, confirm that little has improved for the community over the past two decades.

Despite the fact that Arab-Canadians are overall a well-integrated population, they still face unacceptably high levels of prejudice and discrimination. And despite being among the most well-educated of Canada’s minority groups, they continue to suffer chronic, disproportionate unemployment and underemployment. Often conflated with Muslim Canadians, Arab-Canadians are unrecognized, under-valued, under-served and under-resourced, often invisible to political leaders and public initiatives to address systemic racism.

To address these long-standing systemic problems, governments at all levels must begin to acknowledge the specific problem of anti-Arab racism, and incorporate this perspective into policies that seek to eliminate racial discrimination, inequality, and the racialization of poverty. In part, this means that governments must do better at collecting data on anti-Arab racism and standardizing the reporting of anti-Arab incidents. The Arab-Canadian community rarely report hate crimes or their experiences of discrimination to authorities, fearing retaliation or the possibility that they will not be believed. Many believe that racism is an expected part of life in Canada. Therefore, governments must also do better at improving reporting options for victims of anti-Arab racism. This includes resourcing Arab community organizations to receive reports from community members, who can then forward reports of racist incidents to law enforcement or other agencies and provide victims with necessary support. Law enforcement receiving these complaints should also be required to complete adequate training on anti-Arab racism (i.e. history, context, effects). The federal government should also provide grants to universities to research anti-Arab racism, which would address the knowledge gap and enable better public policy.

Governments and social service agencies should provide access to Arab-language services and resources, including Arabic-language legal aid clinics and immigrant support centres that cater specifically to the Arab-Canadian community. Such programs will help the most vulnerable members of the community, and those most susceptible to anti-Arab racism.

The federal government must enact policies to eliminate the barriers that Arab-Canadians face in terms of accessing services and employment. Programs that ensure equitable hiring of Arab-Canadians within the Federal Public Service should be at the forefront of such efforts, and all levels of government must seek to improve the employment prospects of foreign-trained professionals. The latter can be addressed by government and professional societies working together to assess the comparability of foreign education and credentials, and creating more streamlined paths for professional integration. In the long-term, the federal government should develop an anti-racism impact assessment framework – one that recognizes anti-Arab racism – to help eliminate unconscious bias in proposed policies, programs, and decisions.

To help combat negative Arab stereotypes, governments and public school boards should include anti-Arab racism education and programming to their existing anti-hate and diversity programs. Such public awareness campaigns must promote Arab-Canadian inclusion, and foster cross-cultural understanding. Governments at all levels should also institute cultural competency training for individuals in key public service roles (e.g. judges, public security forces, etc.) giving these professionals the opportunity to learn about and connect with the Arab-Canadian community and understand the systemic discrimination and barriers faced by the community and how not to perpetuate these forms of oppression in their work.

Finally, governments must recognize that anti-Arab racism is deeply connected to public policy at home and abroad. Resources must be put into investigating and dismantling law enforcement and national security measures which have targeted Arab-Canadians and other racialized communities with racial profiling and disproportionate scrutiny. Foreign policy which contributes to ongoing violence and marginalization of Arabs, such as Canada’s unconditional support for Israel despite its occupation, denial of refugee rights, and racist measures against Palestinians, must be overhauled and replaced with a genuinely human rights-based approach.

The contributions of the Arab-Canadian community in many fields including culture, science, business, politics and the arts have greatly added to Canada’s success in these sectors. The Arab-Canadian community is vibrant, eager to excel, and growing quickly. Yet as long as many in this community remain marginalized and misunderstood, Canada will fail to realize its own true social, cultural and economic potential.

NOTES

[1] EKOS is a full-service consulting practice, founded in 1980, which has evolved to become one of the leading suppliers of evaluation and public opinion research for the Canadian government. EKOS specializes in market research, public opinion research, strategic communications advice, program evaluation and performance measurement, and human resources and organizational research.

[2] Houda Asal, Identifying as Arab in Canada: A Century of Immigration History, Fernwood Press: Halifax, 2020.

[3] It is also useful to note that the survey was conducted before the 2021 federal election, which saw a significant rise in the popular vote support for the People’s Party of Canada (PPC), and a significant decrease in the popular vote support of the Green Party of Canada. Given the 2021 election results, it may be advisable to include the PPC as a possible choice in the survey question about respondents’ political party of choice in future surveys.

[4] Ghada Mandil, “Insights into the Arab Population in Canada Based On the 2016 Census Data,” Canadian Arab Institute, August 2019, https://www.canadianarabinstitute.org/census; Statistics Canada, “Census Profile, 2016 Census,” accessed October 14, 2021, https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2016/dp-pd/prof/index.cfm?Lang=E

[5] Canadian Arab Institute, “Who are Arab Canadians,” accessed October 14, 2021, https://www.canadianarabinstitute.org/who-are-arab-canadians

[6] Ghada Mandil, “Insights into the Arab Population in Canada Based On the 2016 Census Data,” Canadian Arab Institute, August 2019, https://www.canadianarabinstitute.org/census; Statistics Canada, “Census Profile, 2016 Census,” accessed October 14, 2021, https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2016/dp-pd/prof/index.cfm?Lang=E

[7] Ibid.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Steven Salaita, Anti-Arab Racism in the US: Where it comes from and what it means for politics today, Pluto Press, 2006, pp. 12-13.

[10] Statistics Canada, “The Arab Community in Canada,” August 14, 2007, archived, https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/89-621-x/89-621-x2007009-eng.htm; Baha Abu-laban, “Arab Canadians,” The Canadian Encyclopedia, last edited December 16, 2013, https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/arabs;

[11] Houda Asal, Identifying as Arab in Canada: A Century of Immigration History, Fernwood Press: Halifax, 2020, pp. 2-3.

[12] Asal, Identifying as Arab in Canada, p. 210.

[13] Asal, Identifying as Arab in Canada, p. 209.

[14] Asal, Identifying as Arab in Canada, p. 209.